The latest research on honey bees by a researcher from Monash University provides the answer to whether the honey bee’s iconic waggle dance is learned or innate.

As we progress through life, we learn many essential behaviours from more experienced people around us. For example, through observing adults, we go from being babbling babies, to using single words, to speaking in full sentences.

This is an example of social learning. And it turns out it isn’t unique to our species.

Honeybees also have a language, expressed through dance, which they use to communicate the location and quality of food sources to hive mates. This behaviour plays a crucial role in the functioning of a hive, which can sometimes have more than 60,000 bees.

Today, a new study published in Science reveals honey bees perfect this dance language by learning from more experienced bees.

What is the ‘waggle dance’?

In 1973, Professor Karl von Frisch won the Nobel Prize in Physiology for decoding the dance of the honey bee, termed the “waggle dance”. This dance consists of a series of movements forager honey bees perform to nest mates in a hive.

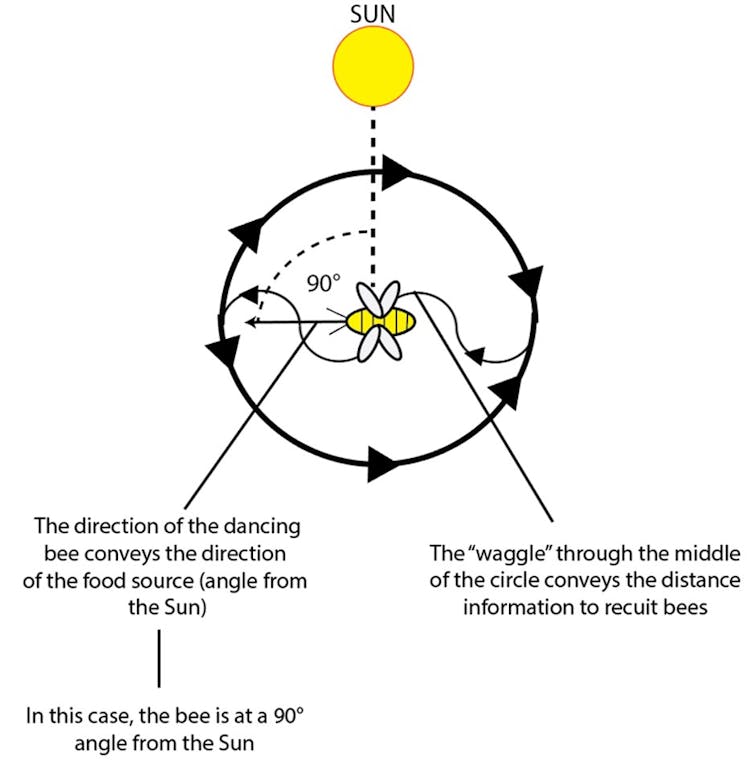

The dance communicates various information about a bee’s foraging trip, including the food source’s distance and direction from the hive, the angle from the sun, and the quality of the resource. It’s performed in a repetitive figure-eight movement.

Read also: Bees for Development Ghana starts Bee the Voice Project to empower women

The forager positions herself perpendicular to the Sun in the direction of the food source, thereby demonstrating its direction. She also performs a “vibration” through the centre of the figure eight, which demonstrates how far the source is.

This behaviour is an interesting example of a complex, informative and co-operative communication style among insects. But, until now, experts didn’t know the extent to which it is learnt, as opposed to innate.

Nature vs nurture?

To find out, a team of researchers from China and the US put some bees to the test. They created hives containing young novice bees (one day old) that had never seen a waggle dance before, and hives containing both novice bees and experienced bees (20 days old).

They placed the hives 150 metres away from a feeder of sugar water: the food source. This placement was important, as it would allow the researchers to assess how accurately the forager bees were dancing to convey information to their hive mates.

The team observed the first dances of novice bees, in both the novice and mixed colonies. Then, after another 20 days, they observed them again.

They found the first dances of bees in the novice colonies overestimated the distance of the food source, were less accurate in communicating direction and were more disordered compared to the first dances of novice bees from the mixed colonies.

After 20 days, when the dancers from both types of colonies were more experienced, the bees in the novice hive had decreased their directional errors and their dances were less disordered. However, they still underperformed compared to their counterparts in the mixed colonies.

Early experience sets a bee up for life

These findings show the waggle dance is indeed innate since it was performed by novice honey bees that had never seen it before.

However, bees that had undergone social learning from more experienced foragers were more accurate and ordered dancers. Even after gaining foraging and dancing experience, the bees in the novice colonies could not dance as well as those that had undergone social learning.

Therefore, the opportunity to observe experienced bees dancing at a young age will determine a bee’s capability to perform accurate dances for the rest of its short life.

Read also: Honey bees: How to repel 7 ruthless pests that eat them

We know from past studies there are different dialects across honeybee species – and dialects indicate a language has been at least partially learned. This new research strengthens the evidence for social learning among honeybees, prompting interesting new questions about how nature and nurture overlap to form this social insect’s complex culture.

Author

Scarlett Howard

Lecturer, Monash University

Scarlett Howard receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) and has previously received funding from the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship, RMIT University, Fyssen Foundation, L’Oreal-UNESCO for Women in Science Young Talents French Award, Deakin University, Monash University, Hermon Slade Foundation, and the Australian Academy of Sciences. She is affiliated with Pint of Science Australia.